Bulgyo Musool - Buddhist Martial Arts?

An essay by Most Ven. Sunyananda Dharma, 9th Dan

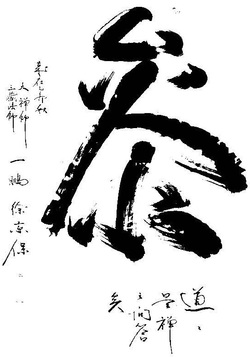

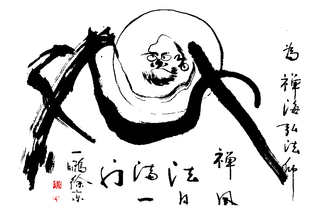

Calligraphic representation of Bodhidharma

Calligraphic representation of Bodhidharma

by the Ven. Dr. Il Bung Seo Kyung Bo

At first glance, Buddhism and martial arts may seem like two pursuits at odds, rather than existing in kindred harmony. After all, Buddhism is a spiritual practice espousing the tenets of compassion and non-violence, whereas the very word martial (by means of its etymology) conveys a sense of war and destruction. In spite of the seeming dichotomy between the two, Buddhism and Martial Arts have a long history as complimentary endeavors oft engaged congruently by Buddhist Monastics in China, Korea and Japan.

Some 1500 years ago it is purported that an Indian monk known as Bodhidharma traveled to China, taking up residence in what is commonly known to English speaking world as the Shaolin Temple (Korean: Sorimsa / Japanese: Shorinji). Upon Bodhidharma's arrival at Shaolin, legend has it that he found the community of monks practicing there in a condition lacking both physical stamina and mental clarity. In answer to the lethargic state of the monks of Shaolin, Bodhidharma is said to have introduced a set of physical exercises that began the codification of martial arts as we know it today, in addition to the experiential insight based teachings that eventually came to be known as Zen (Korean: Seon / Chinese: Chan) Buddhism.

In the present day, the feats of mental skill and martial prowess demonstrated by the Shoalin monks have been immortalized through world tours, pop culture and martial arts media coverage. The fighting monks of Korean history and the Zen savvy warriors of Japan’s feudal past are known to almost all martial arts practitioners of any tenure. Yet, while the legends of Bodhidharma and the Buddhist temple origins of martial arts are propagated in the histories of almost all traditional styles, the actual practice of Buddhist Martial Arts in the west remains virtually unknown. Whilst a great many contemporary martial arts teachers pay lip service to the promise of developing the trifecta of mind, body and spirit through pugilistic tutelage, the connection between executing numerous techniques, forms and kihaps and any inkling of spiritual development is oft tenuous at best, and anything but always completely ancillary.

In spite of the widespread lack of substantial connection between martial arts and spiritual practice, there are indeed arts in existence that have fully developed curriculum integrative of physical and spiritual culture simultaneously, handed down for generations in the Buddhist temples of China, Korea, and Japan. Contemporary Korean Buddhist Martial Arts came into existence in the early 1960's following the end of Japanese occupation of Korea as native Korean martial arts and spiritual endeavors were once again allowed to be practiced and researched opening (having been suppressed from 1876-1945) as an amalgamation of skills and spiritual teachings that had been handed down from antiquity. (See: History).

Some 1500 years ago it is purported that an Indian monk known as Bodhidharma traveled to China, taking up residence in what is commonly known to English speaking world as the Shaolin Temple (Korean: Sorimsa / Japanese: Shorinji). Upon Bodhidharma's arrival at Shaolin, legend has it that he found the community of monks practicing there in a condition lacking both physical stamina and mental clarity. In answer to the lethargic state of the monks of Shaolin, Bodhidharma is said to have introduced a set of physical exercises that began the codification of martial arts as we know it today, in addition to the experiential insight based teachings that eventually came to be known as Zen (Korean: Seon / Chinese: Chan) Buddhism.

In the present day, the feats of mental skill and martial prowess demonstrated by the Shoalin monks have been immortalized through world tours, pop culture and martial arts media coverage. The fighting monks of Korean history and the Zen savvy warriors of Japan’s feudal past are known to almost all martial arts practitioners of any tenure. Yet, while the legends of Bodhidharma and the Buddhist temple origins of martial arts are propagated in the histories of almost all traditional styles, the actual practice of Buddhist Martial Arts in the west remains virtually unknown. Whilst a great many contemporary martial arts teachers pay lip service to the promise of developing the trifecta of mind, body and spirit through pugilistic tutelage, the connection between executing numerous techniques, forms and kihaps and any inkling of spiritual development is oft tenuous at best, and anything but always completely ancillary.

In spite of the widespread lack of substantial connection between martial arts and spiritual practice, there are indeed arts in existence that have fully developed curriculum integrative of physical and spiritual culture simultaneously, handed down for generations in the Buddhist temples of China, Korea, and Japan. Contemporary Korean Buddhist Martial Arts came into existence in the early 1960's following the end of Japanese occupation of Korea as native Korean martial arts and spiritual endeavors were once again allowed to be practiced and researched opening (having been suppressed from 1876-1945) as an amalgamation of skills and spiritual teachings that had been handed down from antiquity. (See: History).

|

Being outwardly a pugilistic form, the study of Buddhist Martial Arts begins by learning the physical forms of self-defense, whilst simultaneously engaging the “great questions of life and death”. A proper teacher will plant the seeds of ganhwa seon (kanhua chan), or “questioning introspection” from the onset of a student's practice. Generally the entry into ganhwa introspection comes in the form of question a student on their motivations for practice. Inevitably, each student of so called “martial arts” comes to participate as a means to gain self-defense ability, and/or physical fitness (and their accompanying ancillary benefits, such as self-confidence, mental focus, recreational fellowship etc). With the latter in mind, students are prompted to delve into their motivations of study and the karmic chains of cause-and-effect that forged them. For instance, if a student is primarily interested in self-defense, they may be questioned as to why that is important to them, and why they would need to defend themselves from another human being, and what an potential attackers motivations for seeking to cause harm might be. In this, the student comes to the direct realization of the interconnectedness of all sentient life, in the innate desire to thrive (existing in a state of happiness, and the avoidance of suffering). If a student is primarily motivated by an interest in an active form of physical exercise for fitness sake, they may be prompted to delve into their motivations for securing physical health, be they out of a desire for longevity or for gaining the approval of others (perhaps society at large).

|

Through continual questioning, this type of student comes to the realization that life inherently involves sickness (the decline of health), aging and eventually death, and further that the independent self is an illusion (anatman), that all phenomena arise as aggregates, and that the root of suffering stems from holding, and desiring to and for ever-changing illusory forms of things.

Fundamentally, it is very easy to instruct a person in the methods of how to injure, maim and kill, however the student of Buddhist Martial Arts is instructed in the more difficult, yet ultimately more fulfilling path of killing (transcending) their own ego. In this, Buddhist Martial Arts practice is spirituality in physical form, somatic dharma; skillful means to point the way toward awakening.

What is Zen?

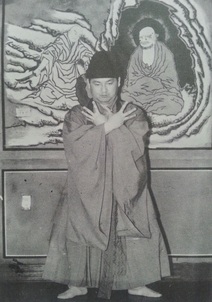

Grandmaster Lee Han Chul demonstrating 'Kicho Chagi' in traditional Zen Buddhist robes.

Grandmaster Lee Han Chul demonstrating 'Kicho Chagi' in traditional Zen Buddhist robes.

Zen meditation is inherently non-religious in the traditional Western usage of the word and is therefore devoid of any form of worship or deity homage; rather Zen is a process acutely focused on the practical realization of engaged, fulfilled, compassionate and joyous living through present-minded awareness, acceptance and action. Simply moment-by-moment, what is this?

Zen practice means to put everything down. From a Western source, to paraphrase Jesus Christ in Mark 8:18, most of us have eyes yet do not see, have ears and fail to hear. Only when we move beyond our expectations and our projections of truth, can the actual truth of this very moment be revealed. Not to get too cliche, but we must “empty our cups”. Emptiness is openness! If we’re seeking for something beyond our current understanding, we must relinquish all things, both ‘good’ and ‘bad’; everything that we’re holding and attaching to; everything that we’re checking and making. All of our thoughts, ideas and opinions must be set aside so that we can see what’s left.

With that said, Zen isn’t a process to engage outside of our daily life and circumstances to somehow overcome it/them. Rather, Zen is the practice of immersing ourselves fully in the experience of our daily lives, moment-by-moment directly perceiving reality as it is, outside of the dichotomies and delusions of our minds. Zen is, in every aspect, a celebration of the moment-by-moment miracle that is each and every instant of our wonder-filled existence.

Zen practice means to put everything down. From a Western source, to paraphrase Jesus Christ in Mark 8:18, most of us have eyes yet do not see, have ears and fail to hear. Only when we move beyond our expectations and our projections of truth, can the actual truth of this very moment be revealed. Not to get too cliche, but we must “empty our cups”. Emptiness is openness! If we’re seeking for something beyond our current understanding, we must relinquish all things, both ‘good’ and ‘bad’; everything that we’re holding and attaching to; everything that we’re checking and making. All of our thoughts, ideas and opinions must be set aside so that we can see what’s left.

With that said, Zen isn’t a process to engage outside of our daily life and circumstances to somehow overcome it/them. Rather, Zen is the practice of immersing ourselves fully in the experience of our daily lives, moment-by-moment directly perceiving reality as it is, outside of the dichotomies and delusions of our minds. Zen is, in every aspect, a celebration of the moment-by-moment miracle that is each and every instant of our wonder-filled existence.

Somatic Zen?

Korean Buddhist monks practicing 'Johk Bahng Uh Sool' (Defense against kick techniques) in front of a stone monument inscribed with the calligraphy of the Ven. Dr. Il Bung Kyung Bo Seo.

Korean Buddhist monks practicing 'Johk Bahng Uh Sool' (Defense against kick techniques) in front of a stone monument inscribed with the calligraphy of the Ven. Dr. Il Bung Kyung Bo Seo.

It seems that the majority of the Zen Buddhist community holds a special reverence for the practice of “just sitting”, and its purported place as the entirety of Zen practice. In that line, I've become acquainted with many in the Zen community holding to notions, that in order for a person to be a true practitioner (let alone teacher) of Zen, one must have sat in meditation for hundreds upon hundreds of logged hours, and in that, perhaps upwards of twenty to forty ninety to one-hundred day retreats (Kor. kyolche).

The phraseology “just sitting” is an English rendering of the Japanese term “shikantaza”, which is the highest ideal specific at least to the Japanese Soto school, and at best to most Japanese Zen institutions. To be clear, Zen itself IS a Japanese word, albeit having been adopted in the west as common terminology by most practitioners regardless of lineage.

Beyond the scope of terminology however, concerning this issue, it's important to note that Japanese Zen is not the be all and end all when it comes to the nature of this practice (of Zen). Indeed in the West, the largest Zen organization has been the Korean rooted Kwan Um School of Zen, founded by Seung Sahn Daejongsa. None-the-less, without delving into the particulars (as least just yet) of what constitutes Zen practice by ethnic tradition, I'm reminded rather, of the story of a certain Zen master upon whose shoulders we all stand (be we practitioners of a Chinese, Korean, Japanese or Vietnamese lineage).

It is said that one day while delivering firewood to a shop, a poor, illiterate, layman heard a customer reciting the Diamond Sutra and spontaneously experienced enlightenment. Of course, Buddhist adepts will immediately recognize this poor, illiterate, non-ordained man as the Sixth Patriarch Huineng, and the teachings attributed to his personage as the Platform Sutra. Huineng had never read or chanted the sutras, never sat in meditation (nor even engaged walking meditation), and he never had an interview with a teacher (Kor. dokcham / Jap. dokusan), yet he spontaneously awakened!

Regardless of the historical factuality of the story of the Sixth Patriarch, what seems important is that his story is one that has been continually transmitted in every lineage of Zen since (at the very least) the 8th century, as a teaching tool to convey the nature of Zen as an expedient and direct path to awakening, not dependent on any particular practice or time spent in study of any particular sutra or teaching. So how then have we seemingly moved from recognizing the already inherent luminous mind (prabhasvara citta) as spoken of by Buddha Shakyamuni himself, to proclaiming some special thing requiring cultivation through a single mode (“just sitting”) of practice over decades?

The wonder of the Zen vehicle rests in its simplicity, in its historical assertion that awakening to our unequivocal “enlightened” Buddha Nature (tathagatagarba) is easily accessible to all beings (seeing as “enlightenment” IS the ordinariness at our core, with only topical delusions to be swept away). However, the disturbing norm today seems to rather be an assertion of (in practicality) having delusion as our core, which rather complexly needs to be mined out and surgically transplanted with “enlightenment”. Of course these former words are a literary exaggeration which are not (to our knowledge) yet propagated literally, however may be inferred by the common standards to which more and more leaders of Zen are clinging.

But what is this “enlightenment” thing really? Perhaps the biggest issue facing the whole of Buddhism itself today is the constitution of our commonly held pinnacle and core of practice. We can find common stories in every Buddhist tradition of so-called enlightened (and widely recognized as such) teachers, masters and patriarchs living lives chocked full of alcohol, drug and sexual abuse, general mismanagement, mistreatment and misuse of their respective sanghas, students and endowed spiritual authority (which may be perversely justified in the common definition of enlightenment as simply “non-dualism”).

In early Buddhism the Pali/Sanskrit word translated as enlightenment is “bodhi”, which references the insight and attainment of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, and by the Buddha's own words at the end of his life, he spent “forty-five years teaching only two things, suffering and its cessation”. So perhaps we can define enlightenment in its earliest Buddhist sense as cultivated insight into the nature of suffering (dukkha) and the attainment of its cessation (nirvana). However, Buddha also taught the concept of “non-self” (anatma) and thus the fundamental lack of any permanent or stable self that can therefore support an unchanging state of “enlightenment”. Therefore, it is often said that there are no enlightened people, only enlightened actions. So perhaps we deem an “enlightened” person as one whose actions demonstrative of non-suffering (nirvana in action), outweigh those demonstrative to the contrary.

Even with this previously defined simple view of “enlightenment” concluded from the basic teachings of early Buddhism, the number of hours, days, months and perhaps decades spent in sitting meditation are irrelevant as qualifiers of “enlightenment”, which is rather demarcated through an individuals actions alone, or perhaps better yet, in conjunction with their explainable insight. But things have not evolved so simply in the Dhyana traditions, “enlightenment” seems to have come to be defined school-by-school with various sets of criteria above and beyond what has been listed here. The latter, perhaps best exemplified with the likes of “public cases” (Kor. kong'an/Jp. ko'an), or checking gates composed of various bits of poetry and prose alongside of bits and pieces of conversations and exchanges between students of the “Golden Age” of Zen in China.

To qualify enlightenment within the practice of Zen, perhaps it's best to actually define the word known as Chan in China, Seon in Korea, Zen in Japan and Thien in Vietnamese. The Sanskrit word dhyana simply refers to a deep and abiding concentration of meditative state. To delve into the meaning of the word in the context of our contemporary practice, it's perhaps worthwhile to also examine the etmyolgy behind the Chinese (where the practice was actually birthed as a fusion of Buddhism and Taosim) transliteration of Chan (禪). The character 禪 is actually composed of two smaller characters, the first (單) meaning “singularity” or “oneness” and the second (示)meaning “to manifest”, thus Chan (dhyana) might be defined as the process of “manifesting oneness”. But oneness of what?

“Oneness” may be defined as a concentrated state of being, transcendent of “this” and “that”, wherein subject and object disappear with the created realm of name and form, and thus too do suffering and not suffering, good and bad, elation and despair. Oneness is a state of being with things just as they are, when they are and for what they are; a place where craving and non-craving, attachment and non-attachment dissipate, falling apart as nirvana naturally thus manifests.

Concerning this aforementioned concentrated/meditative state, interestingly Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn simply defined meditation as “how you keep your mind, moment-after-moment”, which seems to be in line with the notion that manifesting enlightened action and nirvana is not dependent on any particular form of cultivation, be it sitting practice, bowing practice, mantra and chanting practice, the practice of public cases etc. Each of these forms exist solely as skillful means (upaya) to move the practitioner from the sediment realm of deluded intellectualism and cognition to that of the diamond realm of experiential wisdom and insight (prajna).

The various forms of practice that can be found within the varied Zen traditions certainly do not exist in any sort of hierarchy, but rather as skillful means they are relevant only in the context of a practitioners particular state of mind that elicits the utilization of a given form. In other words, “different strokes for different folks”, and different tools for different jobs.

Ultimately, awakening may be likened to dusting a house. Houses all serve fundamentally the same function of providing shelter, comfort and convenience, yet each takes on a different form with different layouts, different furnishings, and differing amounts of dust accumulation. Thus the generic process of dusting a home, may require different tools at different phases and some tools may be entirely unnecessary from one house to another, the same is true of the practice forms of Zen. Therefore Zen cannot be defined in the narrow view of a specific practice form (such as just sitting, or just chanting etc.), but rather as a process of actualizing enlightened action and nirvana in daily life.

The historical precedence concerning being made a teacher in the Zen tradition involves the receipt of some form of mind-to-mind transmission which ultimately places an individual as a successor in a lineage of teachers stretching back to the First Patriarch Bodhidharma, and ultimately Buddha Shakyamuni.

Zen mythology states that Buddha transmitted his dharma to Mahakasyapa during the Flower Sermon on Vulture Peak, thus occurring the first instance of mind-to-mind dharma transmission. In like pattern, each instance of dharma transmission is supposed to certify the recipient as possessing a recognized facsimile of the bodhi mind of Buddha himself, “enlightened successors” if you will.

Concerning the attainment of enlightenment and thus the recognition and appointment of Zen teachers, interestingly the iconic 13th century Japanese Zen Master Eihei Dogen had this to say: "One who regardless of age or length of of his religious career has awakened to the right Dharma and has been approved by an authentic Master. Without giving priority to scriptures and intellectual understanding, he has both extraordinary ability and aspiration. Without clinging to selfish views and without attaching to emotional perceptions, his practice and understanding are in complete accord." Thus neither the “enlightened” state of awakening itself, nor the recognition of an awakened teacher are dependent on any particular form of practice or study or length of time therein engaged, but rather on what Zen Master Seung Sahn taught as “how one keeps their mind, moment-by-moment”. Thusly this form of Dharma propagation, namely Buddhist Martial Arts came into existence, a somatic vehicle of practice which points to the interconnectedness of all phenomena, the very nature of sentient-hood and which cultivates equanimity and boundless compassion.

The phraseology “just sitting” is an English rendering of the Japanese term “shikantaza”, which is the highest ideal specific at least to the Japanese Soto school, and at best to most Japanese Zen institutions. To be clear, Zen itself IS a Japanese word, albeit having been adopted in the west as common terminology by most practitioners regardless of lineage.

Beyond the scope of terminology however, concerning this issue, it's important to note that Japanese Zen is not the be all and end all when it comes to the nature of this practice (of Zen). Indeed in the West, the largest Zen organization has been the Korean rooted Kwan Um School of Zen, founded by Seung Sahn Daejongsa. None-the-less, without delving into the particulars (as least just yet) of what constitutes Zen practice by ethnic tradition, I'm reminded rather, of the story of a certain Zen master upon whose shoulders we all stand (be we practitioners of a Chinese, Korean, Japanese or Vietnamese lineage).

It is said that one day while delivering firewood to a shop, a poor, illiterate, layman heard a customer reciting the Diamond Sutra and spontaneously experienced enlightenment. Of course, Buddhist adepts will immediately recognize this poor, illiterate, non-ordained man as the Sixth Patriarch Huineng, and the teachings attributed to his personage as the Platform Sutra. Huineng had never read or chanted the sutras, never sat in meditation (nor even engaged walking meditation), and he never had an interview with a teacher (Kor. dokcham / Jap. dokusan), yet he spontaneously awakened!

Regardless of the historical factuality of the story of the Sixth Patriarch, what seems important is that his story is one that has been continually transmitted in every lineage of Zen since (at the very least) the 8th century, as a teaching tool to convey the nature of Zen as an expedient and direct path to awakening, not dependent on any particular practice or time spent in study of any particular sutra or teaching. So how then have we seemingly moved from recognizing the already inherent luminous mind (prabhasvara citta) as spoken of by Buddha Shakyamuni himself, to proclaiming some special thing requiring cultivation through a single mode (“just sitting”) of practice over decades?

The wonder of the Zen vehicle rests in its simplicity, in its historical assertion that awakening to our unequivocal “enlightened” Buddha Nature (tathagatagarba) is easily accessible to all beings (seeing as “enlightenment” IS the ordinariness at our core, with only topical delusions to be swept away). However, the disturbing norm today seems to rather be an assertion of (in practicality) having delusion as our core, which rather complexly needs to be mined out and surgically transplanted with “enlightenment”. Of course these former words are a literary exaggeration which are not (to our knowledge) yet propagated literally, however may be inferred by the common standards to which more and more leaders of Zen are clinging.

But what is this “enlightenment” thing really? Perhaps the biggest issue facing the whole of Buddhism itself today is the constitution of our commonly held pinnacle and core of practice. We can find common stories in every Buddhist tradition of so-called enlightened (and widely recognized as such) teachers, masters and patriarchs living lives chocked full of alcohol, drug and sexual abuse, general mismanagement, mistreatment and misuse of their respective sanghas, students and endowed spiritual authority (which may be perversely justified in the common definition of enlightenment as simply “non-dualism”).

In early Buddhism the Pali/Sanskrit word translated as enlightenment is “bodhi”, which references the insight and attainment of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, and by the Buddha's own words at the end of his life, he spent “forty-five years teaching only two things, suffering and its cessation”. So perhaps we can define enlightenment in its earliest Buddhist sense as cultivated insight into the nature of suffering (dukkha) and the attainment of its cessation (nirvana). However, Buddha also taught the concept of “non-self” (anatma) and thus the fundamental lack of any permanent or stable self that can therefore support an unchanging state of “enlightenment”. Therefore, it is often said that there are no enlightened people, only enlightened actions. So perhaps we deem an “enlightened” person as one whose actions demonstrative of non-suffering (nirvana in action), outweigh those demonstrative to the contrary.

Even with this previously defined simple view of “enlightenment” concluded from the basic teachings of early Buddhism, the number of hours, days, months and perhaps decades spent in sitting meditation are irrelevant as qualifiers of “enlightenment”, which is rather demarcated through an individuals actions alone, or perhaps better yet, in conjunction with their explainable insight. But things have not evolved so simply in the Dhyana traditions, “enlightenment” seems to have come to be defined school-by-school with various sets of criteria above and beyond what has been listed here. The latter, perhaps best exemplified with the likes of “public cases” (Kor. kong'an/Jp. ko'an), or checking gates composed of various bits of poetry and prose alongside of bits and pieces of conversations and exchanges between students of the “Golden Age” of Zen in China.

To qualify enlightenment within the practice of Zen, perhaps it's best to actually define the word known as Chan in China, Seon in Korea, Zen in Japan and Thien in Vietnamese. The Sanskrit word dhyana simply refers to a deep and abiding concentration of meditative state. To delve into the meaning of the word in the context of our contemporary practice, it's perhaps worthwhile to also examine the etmyolgy behind the Chinese (where the practice was actually birthed as a fusion of Buddhism and Taosim) transliteration of Chan (禪). The character 禪 is actually composed of two smaller characters, the first (單) meaning “singularity” or “oneness” and the second (示)meaning “to manifest”, thus Chan (dhyana) might be defined as the process of “manifesting oneness”. But oneness of what?

“Oneness” may be defined as a concentrated state of being, transcendent of “this” and “that”, wherein subject and object disappear with the created realm of name and form, and thus too do suffering and not suffering, good and bad, elation and despair. Oneness is a state of being with things just as they are, when they are and for what they are; a place where craving and non-craving, attachment and non-attachment dissipate, falling apart as nirvana naturally thus manifests.

Concerning this aforementioned concentrated/meditative state, interestingly Korean Zen Master Seung Sahn simply defined meditation as “how you keep your mind, moment-after-moment”, which seems to be in line with the notion that manifesting enlightened action and nirvana is not dependent on any particular form of cultivation, be it sitting practice, bowing practice, mantra and chanting practice, the practice of public cases etc. Each of these forms exist solely as skillful means (upaya) to move the practitioner from the sediment realm of deluded intellectualism and cognition to that of the diamond realm of experiential wisdom and insight (prajna).

The various forms of practice that can be found within the varied Zen traditions certainly do not exist in any sort of hierarchy, but rather as skillful means they are relevant only in the context of a practitioners particular state of mind that elicits the utilization of a given form. In other words, “different strokes for different folks”, and different tools for different jobs.

Ultimately, awakening may be likened to dusting a house. Houses all serve fundamentally the same function of providing shelter, comfort and convenience, yet each takes on a different form with different layouts, different furnishings, and differing amounts of dust accumulation. Thus the generic process of dusting a home, may require different tools at different phases and some tools may be entirely unnecessary from one house to another, the same is true of the practice forms of Zen. Therefore Zen cannot be defined in the narrow view of a specific practice form (such as just sitting, or just chanting etc.), but rather as a process of actualizing enlightened action and nirvana in daily life.

The historical precedence concerning being made a teacher in the Zen tradition involves the receipt of some form of mind-to-mind transmission which ultimately places an individual as a successor in a lineage of teachers stretching back to the First Patriarch Bodhidharma, and ultimately Buddha Shakyamuni.

Zen mythology states that Buddha transmitted his dharma to Mahakasyapa during the Flower Sermon on Vulture Peak, thus occurring the first instance of mind-to-mind dharma transmission. In like pattern, each instance of dharma transmission is supposed to certify the recipient as possessing a recognized facsimile of the bodhi mind of Buddha himself, “enlightened successors” if you will.

Concerning the attainment of enlightenment and thus the recognition and appointment of Zen teachers, interestingly the iconic 13th century Japanese Zen Master Eihei Dogen had this to say: "One who regardless of age or length of of his religious career has awakened to the right Dharma and has been approved by an authentic Master. Without giving priority to scriptures and intellectual understanding, he has both extraordinary ability and aspiration. Without clinging to selfish views and without attaching to emotional perceptions, his practice and understanding are in complete accord." Thus neither the “enlightened” state of awakening itself, nor the recognition of an awakened teacher are dependent on any particular form of practice or study or length of time therein engaged, but rather on what Zen Master Seung Sahn taught as “how one keeps their mind, moment-by-moment”. Thusly this form of Dharma propagation, namely Buddhist Martial Arts came into existence, a somatic vehicle of practice which points to the interconnectedness of all phenomena, the very nature of sentient-hood and which cultivates equanimity and boundless compassion.